Solid Modernity – A personal and political reflection on Zygmunt Bauman

By Alex Sobel / @alexsobel

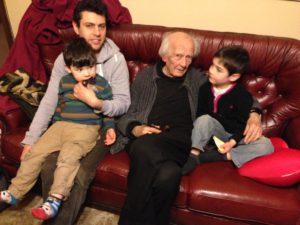

Alex and his family enjoy a moment with Zygmunt

My family’s journey mirrored that of Zygmunt Bauman’s: from Poland to Israel then to Leeds. However it wasn’t until the last, the City we both share, that our families came into contact. My father was a friend of Leon Sfard from Poland who married Zygmunt’s eldest daughter Anna, my father met Leon in Israel as he was preparing to come to Leeds to study at the University in 1972. Leon told my father that his father-in-law had just moved there to be Chair of Sociology. So my newly arrived parents went to a whitewashed house on the Otley Road to meet Zygmunt, he greeted them generously inviting them into his home – thus, a bond was formed and a friendship created which lasted this last 44 years.

Later when I was born the first person to see me after my own parents was Zygmunt and my childhood days are laced with memories of visiting his house, its ramshackle garden, its front room laden with books and kitchen where his wife Janina always offered a small child far more of Zygmunt’s delicious cooking than he could eat. My earliest memories are of a man who always wanted me to stand still so he could take a photo for my parents; I vividly recall going to watch him take photos of people playing with the giant chess pieces outside Leeds Library. Visits to the house were always preceded with quiet warnings about my behaviour, with the occasional reminders of how Zygmunt was a great man, a brilliant thinker.

At the time I wasn’t sure that taking photos and smoking a pipe made you so great, but I was always welcomed into the friendliest of homes where people were animated and interested in life and the world. My family moved around the country, but we always returned to visit Zygmunt and the Baumans in that same house, a house I last visited less than a year ago. Zygmunt, his family home and the myriad interesting conversations were one of the ever present things in my life, a symbol of solidity in a liquid world. Whilst thinking of Zygmunt it feels that that solidity has now become liquid with his passing.

It was my great fortune that Zygmunt’s ascent into the public consciousness and my becoming politically aware coincided. On becoming a Student Union Sabbatical Officer and joining the Labour Party, Zygmunt always took the time to ask me my views as well as offering me a Whisky alongside copious amounts of food. We never talked deeply about his books rather the politics of the day and its effect on society. His way was never to cajole or tell you what to think, instead he would listen and reply with immense insight, I would rarely, if ever, leave his house without an article he had written or book he had recommended.

The copies of Howard Zinn and Paolo Freire are books I will always treasure, offering a very solid reminder of Zygmunt in our fluid world. I was always hugely optimistic about our immediate political future and didn’t think things would work out for the worst, Zygmunt’s own view was slightly more pessimistic – certainly about what was happening or what may happen next. But, he had a profoundly optimistic view in that if we struggled and fought for our ideas we could create a more just society, similar to that his generation had created after the utter desolation of the War. His encouragement to think around a problem meant that when meeting others who had read, or studied him, we immediately have a shared language straight and shared space to exchange ideas.

The loss of both a physical and cultural public space, an interconnected but rootless world, growing insecurity of every kind – a life where landscape constantly changes around you – Zygmunt’s interpretation of modern life’s malady is one familiar to us now.

He coined the term ‘liquid life’ to express this back in the late 90s, but it exploded into the public consciousness after the 2007 crash.

His description remains vividly in the imagination, especially given that traditional social and cultural ties are being eroded, how we relate to each other is being replaced by individual consumerism and built in obsolescence of goods requiring incessant replacing or improving simply to stand still. Zygmunt was right in his analysis of an economic system based on flexibility and precarious employment, when the system crashed this became all too obvious.

Zygmunt wrote about those involuntary participants of the game who cannot afford or don’t want to move with liquid life and the bitterness it can lead to. The ultimate fall-out from this hit us on the 24th June last year with the outcome of the UK’s Referendum on European Union Membership.

Those who played the game were equally ill served by it, becoming unable to buy a house even gain secure tenure in their homes, to secure stable employment.

The desire for such employment is natural, but what is on offer is a contract with only the minimum number of hours guaranteed – allowing the creators of liquid life to recover their position. Zero Hhours contracts, therefore, never help improve the lives of those employed on them and they are now stranded twice as the ability to move across boundaries is being seemingly withdrawn from them. Thus, they have neither security nor freedom of movement.

Zygmunt wrote ‘There are no ‘natural borders’ any more, nor are there obvious places to occupy.’

This line encapsulates two of his passions around the disparity of freedom of movement in society and the loss of public spaces, alongside the interconnected nature of the two. He felt that accelerating disconnection in modern society has been produced and replicated thanks to the ability of elites to move capital, as directing work anywhere in the world ensures that workers have to chase it on ever worsening terms.

At the same time this trapped people in spaces further accelerating consumerism and shrinking those public spaces where people can ‘meet face-to-face, engage in casual encounters, accost and challenge one another, talk, quarrel, argue or agree, lifting their private problems to the level of public issues’.

We on the left are facing a time where a very distinct line is being drawn between those who want to build a wall around economies and those who want a just settlement by improving workers conditions around the world.

Those who seek to impose a simple and nostalgic version of protectionism seek to restrict our freedom of movement in the hope that the effects of globalised capital can be reversed. But in one nation after another the creation of a more just society has only ever come about through fighting for better, more secure employment for all workers – no matter where they are from – and creating public spaces which engender a stronger collective society. I know which side Zygmunt was on, the side which does not pit workers against each other on the basis of ancestry. This is something which will not be lost on EU workers living in the UK as they worry about their current status.

Zygmunt also wrote about our changing political culture in his 2013 Moral Blindness: The Loss of Sensitivity. Here he highlighted and criticised the separation of power and politics saying: ‘Power and Politics live and move in separation from each other and their divorce lurks round the corner’.

He argued that politics has lost its agency. Zygmunt described politics as ‘the ability to see to it that the right things are done’. This is a state that the left have to move towards if we want to regain its purpose and relevance. It is incumbent upon us, as a movement, not to lose sight of this if we are to understand why we are involved in politics. From this we gain insight into the importance of our action for the creation of our desired outcome.

We may have lost Zygmunt at the start of 2017, a year with many challenges ahead for the left. But, we can gain previously unthought of insights from his writing as his stark analysis, with its unfaltering honesty, about the hard challenges we face are needed now more than ever in our endeavour to create the Just Society. Equally, the most solid legacy I can think of is that which I experienced – Zygmunt’s humanity. He showed that we are at our best when we welcome strangers into our home. We warm them not just with whisky but with the animation of kindred spirits, with a problem shared and anecdote offered. We will miss him greatly, but his legacy is something we can all draw strength from, throughout our lives.

Open Labour would like to offer our condolences to Zygmunt’s family and all who knew him. His work will continue to inform our view of how the left should adapt to social and cultural change.

Open Labour’s founding conference is on March 11th – click here to find out more.